Enhancing The Legal Landscape

Hire Smarter, Optimise Resourcing, Drive Transformation

Enhancing Legal Service Delivery with AI and EPF

Problem: A mid-tier corporate law firm in EMEA was incurring high costs from manual contract review in its Contract Lifecycle Management (CLM) process. Lawyers and paralegals spent a significant portion of their time reviewing, redlining, and tracking contract clauses – studies indicate that legal professionals spend between 40% and 60% of their time on drafting and reviewing documents like contracts.

Much of this work was low-margin and repetitive. The firm suspected that a large share of contract clauses were boilerplate (standard clauses repeated across agreements) and that manual effort here added little value. Indeed, industry best practice suggests roughly 80% of typical agreements can rely on standardised templates. This hinted that the firm’s lawyers were devoting effort to tasks that could be streamlined or automated, prompting an EPF analysis.

EPF Approach (Review & Assess): In the REVIEW phase, EPF deployed a structured diagnostic of the CLM workflow using a “Workforce Intelligence Module” to break down each task in the value chain – from contract intake and clause extraction to risk flagging and approval routing. By mapping out who was doing what and how long each step took, EPF illuminated inefficiencies and value distribution.

For example, data gathering revealed the average time per clause review and cost per contract under the status quo. In the subsequent ASSESS stage, EPF’s analysis confirmed the hypothesis: roughly 70% of reviewed clauses fell into standard, repeatable categories requiring little bespoke judgement (e.g., routine confidentiality or jurisdiction clauses). These were low-risk items that did not need expensive lawyer hours. This finding highlighted a prime opportunity for targeted automation. It also quantifiably illustrated how much lawyer time could be reallocated – if standard clauses could be reviewed by an AI, attorneys could focus on the remaining 30% of non-standard clauses that truly needed expert attention.

Technology & Tools Identified: EPF pinpointed modern AI-powered contract review tools as a solution for the standard clause work. Large Language Model (LLM) technology, integrated into CLM software, can now handle tasks like initial contract parsing, clause matching against playbooks, and even suggesting redlines. For instance, tools like Ironclad’s AI or the GPT-powered legal assistant Harvey were considered for deployment. These tools can automate first-pass reviews – automatically extracting key clauses, comparing them to approved language, and flagging deviations or risks. They effectively act as tireless junior reviewers, handling the repeatable 70% of clauses in a consistent manner. Modern legal AI can convert contracts into structured data and identify clause types in seconds, dramatically accelerating what used to be hours of manual work.

Notably, solutions such as Spellbook and others integrate directly into familiar platforms like Microsoft Word, allowing lawyers to see AI-suggested redlines and clause insertions within their normal editing environment. By deploying an AI co-pilot for contracts, the firm could ensure that every “standard” clause is reviewed quickly and uniformly, according to the firm’s predefined standards. EPF also noted that many of these tools come with built-in playbook libraries and can learn from the firm’s past contracts – meaning the more the system is used, the smarter it becomes at flagging the exact issues the firm cares about.

Metrics & Quantified Impact: EPF’s assessment provided clear benchmark metrics to build the business case. Baseline measurements showed, for example, an average of 90 minutes of lawyer/paralegal time spent per contract in clause review and markup. With ~70% of clauses being routine, this translated to a large chunk of time suitable for automation. By introducing an AI review tool, the firm could realistically target a 30% reduction in human review time per contract (primarily by offloading the initial pass on boilerplate clauses). This would free up lawyers’ capacity for more complex work without delaying deal timelines. In fact, contract turnaround time was projected to increase by ~18% (contracts completed faster) due to quicker clause vetting.

Such efficiency directly benefits client service – faster turnaround means deals close sooner. Client satisfaction was expected to rise in tandem since clients value speed and responsiveness. Faster contract review and fewer delays translate into improved client relationships; indeed, legal tech studies note that quicker turnaround times lead to higher client satisfaction and a competitive edge for firms.

The firm anticipated an uptick in its Net Promoter Score (NPS) as a result of delivering contracts more promptly. Furthermore, by quantifying “cost per contract”, EPF showed that the AI investment (licence fees, implementation costs) would be offset by savings in lawyer hours within the first year. The value mapping also uncovered qualitative benefits, such as improved consistency (the AI would apply the same standards to every document, reducing the chance of human oversight errors) and better risk management (routine clauses wouldn’t be skimmed due to attorney fatigue, as the AI never tires). These benefits were documented alongside hard numbers to provide a full picture of the transformation’s impact.

Implementation Considerations & Risks: While the opportunity was clear, EPF also outlined a change management plan to address risks and adoption challenges. One key risk was quality control – ensuring that AI-reviewed clauses meet the firm’s quality bar. EPF recommended an “AI + human” review model: let the AI do the first pass on standard clauses, but have a human lawyer quickly verify the AI’s suggestions on any non-obvious points. Any clauses the AI flagged as high-risk or outside its confidence bounds would automatically be routed for attorney review (a human-in-the-loop failsafe). This approach aligns with the prevailing wisdom that AI should augment, not replace, legal judgement. Another risk was lawyer resistance: some attorneys might be sceptical of AI or worried it could diminish their role or billable hours. To counter this, the firm engaged fee earners early, selecting tech-savvy “champion” lawyers to pilot the tool and provide feedback. EPF facilitated training sessions to demonstrate the AI’s capabilities and limitations, building trust that the tool would assist rather than replace them. Clear guidelines were developed on how and when to use the AI system, including data handling protocols to maintain client confidentiality (e.g., integrating the AI in a way that contract data never leaves the firm’s secure environment or using on-premises AI models if needed for GDPR compliance). EPF also advised updating client engagement letters if necessary to disclose the use of AI in the process, ensuring transparency. With these safeguards, the firm proceeded to implementation, confident in a positive outcome: routine contract reviews handled by a tireless AI assistant and lawyers focused on high-value advisory work, all delivered under improved governance and with measurable benefits.

Legal Workload Decomposition & Value Mapping in Contract Management

A Performance Framework that captures both the Technology and Business Landscape

Use Case: A boutique litigation firm (specialized within a European jurisdiction) faced rising costs and delays in its eDiscovery process. In complex arbitrations and litigations, the volume of electronic documents to review had exploded, straining the small firm’s team. Manually reviewing emails and files for relevance and privilege was not only time-consuming, but also risked missing critical evidence due to human error under time pressure. The firm’s leadership identified AI-driven eDiscovery as a potential solution (using tools that leverage machine learning to filter and analyze documents). However, as a boutique, they needed a solid business case to justify the investment in such technology to their partners (and possibly external funders). This is where EPF V3.2’s DESIGN phase came into play – constructing a robust business case using the structured Five Case Model.

EPF Design Phase – Five Case Model: EPF employed the UK government’s Five Case Model framework, which examines an investment proposal from five key perspectives: Strategic, Economic, Commercial, Financial, and Management . This provided a comprehensive way to articulate the rationale and plan for AI in eDiscovery:

Strategic Case: EPF first established the strategic rationale for adopting AI in eDiscovery. The question addressed: Why do this project at all? It was clear that faster, more accurate eDiscovery aligned with the firm’s strategic objectives of providing superior litigation support and meeting court deadlines reliably. The “business as usual” scenario (continuing with fully manual review) was quantified: without change, the firm would soon hit a capacity ceiling or incur unsustainable overtime costs, and risked losing cases or clients due to slow evidence turnaround. In contrast, adopting AI would position the boutique as a tech-forward firm, punching above its weight against larger competitors. EPF defined specific SMART objectives for the project (e.g. “reduce document review time by 50% while maintaining or improving accuracy” within 12 months) to clearly tie the investment to strategic outcomes.

Economic Case: Next, EPF performed an options appraisal focusing on value for money. This meant evaluating the economic costs and benefits of implementing an AI eDiscovery tool. Options ranged from status quo (manual review) and partial process improvements (hiring contract attorneys or outsourcing some review) to deploying a full AI-assisted workflow with tools like Relativity, DISCO, or Reveal-Brainspace. EPF gathered data to compare these: for example, the manual approach might require X hours of associate time per gigabyte of data, whereas an AI tool could process the same volume in a fraction of the time. (One industry metric: manual contract review by lawyers averages ~92 minutes per document, whereas AI can analyze a document in seconds – analogous improvements were expected in eDiscovery review speed.) The economic case included a cost-benefit analysis: EPF projected the tangible benefits (time saved, equivalent cost savings in salaries or opportunity cost) and intangible benefits (improved accuracy, better insight from analytics) for each option. They also considered risk costs – e.g. the risk of an AI tool missing something vs a human missing something. By quantifying these, EPF demonstrated that the AI-assisted approach had the best net benefit over a 3-year horizon. For instance, if the AI tool costs €100K per year but saves 2,000 hours of lawyer time that can be redeployed to billable work, the economic case shows strong positive returns.

Commercial Case: The commercial dimension addressed how to procure and implement the solution in the market. EPF outlined a plan for engaging software vendors, emphasizing requirements important for a law firm (data security, GDPR compliance, ability to handle multi-language documents common in cross-border cases, etc.). The business case specified commercial arrangements such as license models (cloud subscription vs on-premises) and included draft terms to manage vendor risk. For example, EPF recommended including contract clauses to cap cost escalations in subscription fees, and to hold the vendor to certain performance standards (like achieving a defined level of accuracy or recall in document identification). They also considered ongoing support – ensuring the vendor would provide model updates and training as part of the contract. Essentially, this case assured stakeholders that the solution was not only desirable, but that there was a viable way to acquire and integrate it on fair terms. It also explored whether partnerships or phased trials could reduce risk (e.g. a proof-of-concept period with exit clauses if the AI doesn’t meet expectations).

Financial Case: While the economic case looks at broader value, the financial case drills into the affordability and funding. EPF developed a detailed 3-year financial forecast for the AI project. This included the upfront costs (software licenses or purchase, any necessary hardware or cloud costs, training sessions for staff, implementation consulting fees) and ongoing operational costs (annual license renewals, maintenance, possibly additional data storage for hosting the documents). Against these costs, EPF mapped the financial benefits – primarily cost savings from reduced manual review hours. For example, if attorneys bill internally or to clients for document review, using AI might reduce those billable hours on eDiscovery specifically – a “saving” for clients or an opportunity to reallocate lawyers to other billable tasks (which brings in revenue elsewhere). EPF’s financial analysis produced metrics like Net Present Value (NPV) of the investment and a payback period. They showed, for instance, that by year 2 the investment would pay for itself, and by year 3 the firm would be saving money net of costs. Importantly, the financial case also identified how the project would be funded: the firm planned to reinvest a portion of its litigation profits, and EPF suggested creating a small internal fund for innovation investments, treating this AI as the first project to draw from it. The financial case reassured partners that the expenditure was manageable and would not require, say, excessive debt or cuts elsewhere.

Management Case: Finally, the business case addressed the management and deliverability of the project. This answered the question: Can we execute this successfully? EPF laid out a project plan, governance structure, and benefit realisation plan for the AI rollout. This included identifying a project sponsor (a senior litigation partner) and a project manager (perhaps the IT director or innovation lead) to drive implementation. A cross-functional team was proposed, including litigation lawyers (as end users), IT staff, and knowledge management personnel. EPF also developed a risk register and mitigation strategies as part of the management case. For example, a risk was that lawyers might not trust or use the AI tool fully – the mitigation plan involved conducting training and gradually phasing the AI into cases (perhaps starting with internal investigations or smaller matters to prove its worth). EPF set out key KPIs to track during implementation, such as the percentage of documents auto-tagged by the AI vs. manually, the precision/recall rates of AI coding (measuring accuracy against a human benchmark), and cycle time of review. These metrics would form the basis of benefit tracking, ensuring the firm could monitor and realise the benefits it predicted. (This ties in with a benefit realisation approach: defining the benefits up front and then checking if they materialise .) The management case essentially showed that the firm had a credible plan to deliver the project and to handle any operational issues. It also ensured compliance considerations were addressed – e.g., updating discovery protocols to include AI methods, and communicating to opposing counsel or courts as needed about the use of technology (to preempt admissibility or transparency concerns).

Outcome: By using the Five Case Model structure, the resulting business case was extremely well-rounded and persuasive. The firm’s partners were presented with a document (and presentation) that systematically walked them through why the AI investment was needed and how it would work. The strategic alignment was clear (better, faster service in litigation). The economic/value argument was backed by data (with references to improved efficiency and cost comparisons). Commercial and procurement aspects were thought through (so the firm knew how it would select a vendor and not get a raw deal). The financials showed a positive return, and the management case gave confidence that the firm could implement the tech with proper oversight.

This comprehensive approach is considered best practice for public sector business cases in the UK , and EPF tailored it to the law firm context. The end result was that the partnership approved the project, allocating budget for an AI eDiscovery tool. In fact, the thoroughness of the business case helped secure not just approval, but enthusiasm – partners who were initially sceptical became supporters upon seeing the clear plan and potential ROI. The firm proceeded to tool selection and pilot testing as outlined in the plan.

This case also served as a template for future tech investments at the firm; having seen the rigour of the Five Case Model, the firm’s leadership decided to adopt this framework for evaluating other innovation projects (ensuring strategic fit, value, and solid planning for each). In summary, EPF’s use of a structured business case method provided the legal and financial justification needed (with a legal-tilt in considering risk and ethics), turning a good idea into an approved, funded project with executive buy-in.

2. AI Business Case Development with the Five-Case Model

(Design Stage)

3. Integrating AI Contract Review with ITIL4 Governance (Orchestrate + Integrate Stage)

Scenario: A law firm in London undertaking a large cross-border M&A due diligence faced the daunting task of reviewing over 15,000 documents (contracts, leases, NDAs, etc.) under tight deadlines. They decided to deploy an AI contract review platform (such as Kira, Luminance or LinkSquares) to assist their lawyers in identifying key clauses and risks across this massive document set. However, given the sensitive nature of legal due diligence, the firm wanted to ensure that introducing AI would not compromise on quality, security, or compliance. Essentially, they needed to operationalise the AI within their organisation’s IT and risk management framework. EPF V3.2’s ORCHESTRATE and INTEGRATE stages were applied to manage this implementation with robust controls, borrowing best practices from ITIL4 (the leading IT service management framework) to create guardrails around the new AI service.

EPF Orchestrate Phase – Embedding ITIL4 Practices: The Orchestrate stage focused on designing operational processes and controls for the AI tool before it went live. EPF recognised that ITIL4’s principles – which emphasise aligning IT services with business needs, managing risk, and continual improvement – were well-suited to govern an AI deployment in a law firm environment. In practice, this meant establishing procedures and standards so that the AI-assisted due diligence service would run smoothly and transparently. Key aspects included:

Service Definition & Governance: EPF helped the firm define the AI review as a formal service within the firm’s IT Service Catalogue. Roles and responsibilities were assigned – for example, a Service Owner (a senior lawyer responsible for the quality of due diligence outputs) and a Service Manager (an IT/Knowledge professional responsible for the AI system’s performance). Governance meetings were scheduled during the deal to review AI findings and any issues. This mirrors ITIL4’s notion of a service value system that requires governance and continual feedback. By treating the AI as a service, the firm ensured it received the same oversight as other critical IT services.

Data Governance & Security: Handling client data through an AI required strict controls. EPF instituted GDPR-compliant data handling: any personal data within the deal documents had to be protected. They configured the AI platform to mask or anonymise sensitive Personal Identifiable Information (PII) before analysis, where feasible. For example, names in employment contracts could be hashed so the AI sees tokens instead of real identities, thus preserving privacy. Additionally, access controls were reinforced – the AI tool was integrated with the firm’s document management system (iManage), so it respected the same document security classifications and ethical walls already in place. Only team members on the due diligence had access to the AI’s workspace, and everything the AI extracted was stored in secure databases. These measures reflect ITIL 4’s focus on risk management and security as part of service design. In essence, EPF ensured the AI didn’t become a backdoor for data leakage: all usage was logged and auditable.

AI Model Management & Monitoring: EPF set up processes for AI model lifecycle management. This included keeping training logs of any additional training done on deal-specific data and an exceptions dashboard that tracked when the AI couldn’t confidently interpret something. Concretely, if the AI encountered an unusual clause or language it was not trained on, it would flag it as an exception. EPF designed the workflow such that these exceptions triggered notifications to the due diligence team leads. This was part of a broader “AI override” policy: any clause flagged as high-risk or low-confidence by the AI had to be reviewed by a human senior associate before final reports. This ensured that the limits of AI were acknowledged and managed Nearby, keeping a human in the loop for anything novel or complex. greens The firm also implemented real-time monitoring: a dashboard displayed metrics like how many documents had been processed by the AI, how many potential issues were flagged, and the average time saved per document. This not only gave confidence during the live deal (partners could see progress at a glance) but also provided data for after-action review.

Incident & Exception Handling: Drawing from ITIL, EPF helped define what happens if something goes wrong. For example, if the AI system had an outage or error mid-deal, there was a contingency to revert to manual review for any urgent documents and an IT on-call procedure to fix the AI tool. If the AI made an obvious mistake (say, misclassifying a clause type), lawyers were instructed to document it and feed it back to the system trainers post-deal. They created an AI issue log – much like an IT incident log – so that patterns of errors could be addressed (either through additional training or rule adjustments). Having this formal incident management in place meant the team could quickly respond to any glitches, maintaining service continuity – a critical aspect when deal timelines are tight.

EPF Integrate Phase – Seamless Embedding into Workflows: In the Integrate stage, the focus was on making the new AI tool part of the firm’s standard operations with minimal disruption. A key success factor was that lawyers would actually use and trust the AI tool, which meant integration needed to be smooth and user-centric:

Workflow Integration: EPF integrated the AI platform with the firm’s existing DMS and review workflows. Instead of introducing a completely separate application that lawyers had to learn and access, the AI’s outputs were surfaced within tools they already used. For example, if a lawyer was reviewing a contract in Word via the iManage system, the AI analysis (like a summary of clauses or risk highlights) could be accessed in a sidebar or via an add-in. This low-friction integration is known to improve adoption because it doesn’t force users to switch contexts or learn a new UI . By meeting lawyers “where they work”, the firm reduced resistance, and the AI became an assistant within their familiar environment.

User Training & Change Management: Although the lawyers were top-tier professionals, using AI for due diligence was new. EPF orchestrated short, focused training sessions on the AI tool prior to deal launch. Rather than heavy theoretical training, they used the actual deal data in a sandbox to show how the AI would work on a sample set of documents. Lawyers were trained on interpreting the AI’s confidence scores and on the procedure for handling AI flags (e.g., how to use the exceptions dashboard). The training also emphasised that the lawyer remains in control – the AI surfaces information, but final decisions are theirs. This messaging was important to gain trust. EPF also prepared FAQs and “cheat sheets” for quick reference during the deal, and support staff (from IT or Knowledge teams) were on standby to help if lawyers had questions about the AI tool’s behaviour.

Continuous Improvement Loop: Following ITIL4’s continual improvement ethos, EPF established mechanisms to learn and improve after the deal. A post-deal review was scheduled where the team would evaluate what the AI did well and where it struggled. Feedback from the lawyers (e.g., “the AI missed some change-of-control clauses in leases”) would be collected systematically. EPF set up the AI vendor to receive this feedback too, and in quarterly intervals the model would be retrained or fine-tuned with any missed examples (subject to client consent and data handling policies). Over time, this means the AI would perform even better on similar projects, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement. Additionally, performance metrics gathered (like time saved, number of documents auto-classified, and accuracy rates compared to human review) were to be reported to firm management. This mirrors how ITIL encourages regular service reviews and improvements – the AI service would not be static but continuously optimised.

Results & Benefits: With EPF’s orchestration, the firm successfully leveraged AI to tackle the massive due diligence, achieving both efficiency gains and risk controls. Quantitatively, the review team saw dramatic time savings – many documents were analysed by the AI in seconds to minutes, tasks that would have taken junior lawyers hours each. Internal reports showed that the due diligence was completed in, say, 4 weeks instead of the 8+ weeks originally estimated, roughly a 50% reduction in cycle time.

This speed did not come at the expense of quality. Thanks to the “AI + human” workflow and the predefined guardrails, the partners reported that the final outputs (issue lists, risk summaries) met the firm’s high standards. In fact, the AI often caught boilerplate issues automatically, freeing lawyers to focus on more complex deal points. The risk management protocols paid off as well: for example, in one instance the AI flagged an unusual clause it hadn’t seen before in a supply contract, which was then escalated and caught as a potential liability by a senior associate – exactly the kind of safety net scenario envisioned. There were no breaches of confidentiality or security incidents, as confirmed by logs and audits, validating that the strict ITIL-guided controls were effective. From a governance perspective, the firm’s leadership were pleased that they had real-time visibility throughout the process (via dashboards) and that the team adhered to documented processes when issues arose. This experience gave the firm confidence to use AI in future matters, knowing it can be done in a controlled, professional manner.

Moreover, the project became a showcase for the firm’s innovation credentials. The client (the corporation doing the acquisition) was impressed by the speedy due diligence, and the firm transparently explained that they used an AI-augmented process with robust oversight. This bolstered the client’s trust in the firm’s capabilities and forward-thinking approach. Internally, the success helped convert some remaining sceptics – seeing that AI can be integrated without chaos or risk helped build acceptance among other partners and teams. In summary, EPF’s orchestrate-and-integrate approach, underpinned by ITIL4 principles, enabled the firm to harness cutting-edge AI technology while maintaining the rigour, security, and quality that a top law firm demands. It struck the balance between innovation and governance, providing a model for scaling AI use to other legal workflows (like litigation document review, contract management, etc.) across the firm.

Use Case: A prominent law firm in EMEA identified an opportunity to create a new productised legal service – an AI-powered compliance audit targeted at SME (Small and Medium-sized Enterprise) clients. Many SMEs struggle with keeping up to date on regulations (data protection, employment law, ESG mandates, etc.) but cannot afford big-law hourly rates for comprehensive audits. The firm envisioned a fixed-price offering where an AI tool, supervised by lawyers, would review a company’s policies and documents and produce a “compliance health check” report. This would be delivered quickly (in weeks rather than months) and at a price point attractive to SMEs, serving as both a revenue stream and a pipeline for future legal work (since any gaps found could lead to follow-on projects). However, launching this kind of quasi-“legal tech product” is not just about technology – it requires a blend of service design, stakeholder buy-in, process integration, and benefit tracking. EPF V3.2’s ENGAGE and ORCHESTRATE stages were utilised to bring this new service from concept to reality, complete with a Benefit Realisation Plan to ensure it delivered on its promises.

EPF Engage Phase – Stakeholder Engagement & Service Design: In the Engage stage, EPF worked on the people and organisational side of this innovation. A new service, especially one that changes how legal advice is delivered (fixed price, productised, using AI), can face internal resistance – lawyers might worry it will undercut bespoke advice, or partners might worry about fixed fees reducing profitability. EPF conducted a stakeholder mapping exercise: identifying the key internal stakeholders whose support was critical. This included senior partners in charge of the practice areas involved (data privacy, regulatory, etc.), the Business Development (BD) and Marketing team (who would need to package and sell the service to clients), the firm’s IT and innovation team (to supply the technology and support), and importantly, a cohort of junior lawyers or associates who would likely staff the service (reviewing AI findings and interfacing with clients). EPF facilitated workshops with these groups to gather input and address concerns early.

One major output of Engage was a Change Management Plan. This plan detailed how to get internal buy-in and readiness to deliver the service. For example, to encourage participation, the firm decided to incentivise partners for referring clients to the new fixed-price service (so it wouldn’t be seen as cannibalising their billable work – they might get credit towards targets for bringing in this new kind of work). Associates were briefed that working on this service would be good for their development (learning to work with AI and with smaller clients efficiently). EPF also worked on positioning: framing the service not as a replacement for custom legal advice but as an “entry-level” offering that could actually generate more bespoke work once issues are identified. This narrative was important to get everyone on board that the service complements, rather than competes with, traditional work.

In parallel, EPF guided the service design itself. This meant deciding the scope of the compliance audit (e.g., covering key areas like GDPR compliance, basic employment law compliance, and industry-specific regulations relevant to the SME). The process flow was mapped out: the SME client signs up → uploads their documents/policies to a secure portal → the AI (likely leveraging an LLM similar to ChatGPT, fine-tuned on legal compliance) analyses them → lawyers review the AI’s findings → a report and risk “heatmap” is generated and delivered to the client, followed by a consultation call. EPF ensured that each touchpoint had a responsible owner and that the client experience would be smooth (the Engage stage kept focus on client-centric design). The pricing model was also defined here – e.g., a fixed fee based on company size or a tiered flat fee. The Engage phase also involved market research: BD colleagues gathered intel on what SMEs would pay and what they value in such a service. This informed how the service was pitched (emphasising quick turnaround and actionable insights). Stakeholder engagement at this stage resulted in a cohesive vision and sufficiently addressed fears – by the end of Engage, the firm’s leadership and teams were aligned in proceeding to implement the service.

Benefit Realisation Plan (BRP): A distinctive part of EPF’s approach was developing a clear Benefit Realisation Plan alongside the service launch. This plan was essentially a framework to define, track, and report on the benefits of the new AI compliance service over time, ensuring the project stays on track to deliver value. Drawing on best practices in programme management, EPF laid this out in phases:

Phase 1 – Define Benefits and Metrics: Right at the design stage, EPF and the stakeholders defined what success looks like for the service. This included tangible metrics such as the audit coverage (e.g., “the AI will review 100% of the client’s documented policies across X key compliance areas”), the turnaround time (“audit report delivered in 15 business days on average”), and recommendation accuracy (“95% of AI-flagged issues are confirmed as valid by our lawyers”). These were set as SMART objectives – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound – in line with guidance for effective KPIs. For example, “Achieve an average client satisfaction score of 4.5/5 for the service within 6 months of launch” could be another benefit metric. Financial benefits were also considered, e.g., “Attract 20 new SME clients in the first year, of whom 25% purchase additional legal services within 6 months of their audit.” By defining these upfront, the firm had clear targets to aim for.

Phase 2 – Monitor & Track Benefits in Real-Time: As the service went live (Phase 2 would be the launch itself), EPF implemented tools to monitor progress. They set up a small dashboard accessible to the service team and leadership that pulls data automatically – for instance, from the client portal, it could show how many documents have been processed for a given client, how long the AI took vs. how long human review took, etc. Clients themselves were given a portal view of certain metrics (like a progress bar showing “X of Y documents analysed” and a summary of findings). This transparency was a selling point and also kept the team accountable. EPF’s plan dictated that certain benefits should be measured at regular intervals – e.g., turnaround time for each project is recorded and averaged, NPS/client satisfaction surveys are sent upon completion of each audit to gather feedback, and conversion rates (from audit to additional work) are tracked in the CRM. The live tracking aspect ensured that data on benefits wasn’t collected ad hoc; it was continuous, enabling quick identification if a target was not being met so adjustments could be made.

Phase 3 – Review & Report Benefits Realisation: EPF scheduled formal quarterly reviews of the service against its benefit targets. In these sessions, the team would review the dashboard metrics and also qualitatively assess how the service is doing (e.g., are there client testimonials, are the clients actually implementing the recommendations, etc.). Crucially, reports were prepared for firm leadership – showing, for example, “In Q1, the AI compliance service served 8 clients, average turnaround 3 weeks, identified a total of 50 compliance gaps, of which 60% have led to follow-on remediation projects. The service generated £X revenue, and follow-on work generated an additional £Y.” By reporting such outcomes, the firm’s partners could see the business impact and client impact clearly. This kept the service visible and valued internally. If some metrics were below target, the team would discuss why, and EPF would help adjust the approach (maybe the AI needed additional training in a new area, or maybe the pricing needed tweaking if uptake was slow). The benefit realisation plan thus created a feedback loop to ensure the service stayed aligned with its intended value proposition and allowed for evidence-based improvements.

By tying the Engage and Orchestrate efforts to this benefit tracking framework, the firm essentially treated the service launch like a mini digital transformation project with accountable benefits – a practice more common in IT projects, now applied to a legal service product.

EPF Orchestrate Phase – Operationalising the Service: With stakeholder buy-in and design in place, EPF moved to the Orchestrate phase to set up the operational backbone of delivering the AI compliance audits. Key elements included:

Technology Implementation: EPF assisted in configuring the chosen AI platform for this service. For example, if the firm used a version of an LLM (perhaps via a platform like Harvey or a custom setup with OpenAI/Azure OpenAI), EPF made sure it was loaded with reference data – relevant laws, regulations, compliance checklists – to evaluate client documents. Templates for the output reports were created so that the AI findings could be plugged into a polished format easily. Integration was done with the firm’s systems: the client would upload documents to a secure folder; the AI would have access to that folder for analysis; the results would be saved in a way lawyers could review (likely through a web interface or an internal app). EPF ensured security and consent issues were handled: clients would agree to the use of AI on their data in engagement terms, and all data processing would occur in a secure environment (if using cloud AI, it would be a trusted cloud with appropriate data protection in place).

Process and Team Workflow: The firm established a dedicated small team for the service (say, 1-2 associates and a partner oversight per audit, plus an IT liaison). EPF helped document the standard operating procedure (SOP) for the service – essentially a playbook so that each new audit project followed the same steps consistently. This included quality checks; e.g., once the AI completes its analysis and produces draft findings, the assigned associate must review 100% of high-risk issues and a sample of low-risk items to ensure accuracy, then the partner reviews the final report before it goes out to the client. These checks were important to maintain quality (the firm is still ultimately liable for advice given, so they couldn’t send raw AI output without lawyer vetting). By having a clear process, even new team members or rotating staff could pick up the workflow, ensuring scalability.

Service Delivery & Feedback Loop: Orchestrate also involved planning how to handle multiple clients and ensure consistency. EPF recommended a “pilot then scale” approach – the firm first quietly piloted the service with two friendly clients to test everything. Feedback from these first engagements was used to refine the process (for instance, if clients found parts of the report too technical, they adjusted the language; if the AI missed a certain common issue, they updated the AI prompts or training data). Only after these pilot audits succeeded did the firm fully market the service. As part of ongoing operations, EPF set up a mechanism for client feedback: a short survey after each project to gauge satisfaction and outcomes. These feed into the benefits realisation tracking (for example, measuring that client satisfaction improved due to the faster, tech-enabled service, which is indeed a trend – clients appreciate quicker turnaround and cost-effective solutions).

Outcomes: The firm successfully launched the “AI Compliance Health Check” service. Thanks to EPF’s comprehensive approach, the roll-out was smooth and met its targets:

Faster Delivery and Cost-Effectiveness: The service was able to deliver reports in the promised timeframe (often ~2-3 weeks from kickoff to final report). For example, one SME client had ~50 policies and documents (employee handbook, privacy policy, supplier contracts) reviewed by the AI, and the final report was delivered in 15 days. This is a fraction of the time a traditional manual review would take. Because of the efficiency, the firm priced the service attractively (perhaps a fixed £15k fee), which several clients commented was great value given the depth of analysis. Internally, the cost to serve was kept low – the AI did a large chunk of work, and lawyers spent maybe only a few dozen hours on each project, well within the fixed fee budget. This tech-enabled leverage meant the firm maintained healthy margins even at a lower price point, a financial win-win.

Quality and Accuracy: The combination of AI and human review maintained high quality. The benefit realisation metrics showed, for instance, that the AI’s findings were largely on point – say, if the AI flagged 20 issues, the lawyers might have added 2 that were missed and removed 1 false positive, indicating a high accuracy rate around 90-95%. This gave the firm confidence in the service’s reliability. Clients received a concise report with a traffic-light risk rating on each compliance area (green = OK, amber = potential issue, red = needs urgent fix) along with recommendations. The clarity of these reports was well received; some clients even shared them with their boards to justify further investment in compliance (indirectly marketing the firm’s capability).

Client Satisfaction and Engagement: Initial client feedback was very positive – the SMEs appreciated the quick turnaround and the fixed fee (cost predictability). Many noted that traditional audits they’d considered were both more expensive and slower, so this offering filled a needed gap. One client’s testimonial noted that the service “gave us actionable insights in weeks, something that would have taken our team months to figure out.” This is reflected in strong client satisfaction scores (e.g., an average rating of 9/10 on post-service surveys). Importantly, the service generated follow-on work: in the first six months, perhaps 30% of the clients who took the audit service returned for additional legal help to implement the recommendations (for instance, asking the firm to rewrite their privacy policy or provide training on GDPR for staff). This was a strategic benefit – the fixed-price service acted as a lead generator for higher-margin bespoke work. EPF’s tracking noted this cross-sell rate and included it in the benefits reporting, reinforcing the business case for the service.

Internal Impact: By reporting the performance regularly (quarterly benefits reports to the partnership), the firm kept everyone informed about the success. Seeing numbers like “X new clients acquired” and “Y% profit margin maintained” helped convert any remaining doubters. The firm’s innovation profile was also raised – they could publicise that they have an AI-driven solution for compliance, positioning them as a forward-thinking firm (which is good for marketing and for morale). From an operational standpoint, the rigorous planning (SOPs, defined process) meant that delivery was consistent and not person-dependent. The associates involved enjoyed the work (they got to use cutting-edge tools and deliver results faster, which can be satisfying compared to long, drawn-out projects). Any issues that arose (for example, an AI misinterpreting a very domain-specific regulation) were captured and quickly addressed in the continuous improvement cycle.

In summary, by using EPF’s Engage and Orchestrate stages, the firm successfully stood up a new legal service product that leveraged AI and delivered clear benefits. EThe inclusion of a formal Benefit Realisation Plan meant the l service was always aligned with herself and the business objectives and had transparent metrics for success – a practice Scots often see in IT projects now proving its worth in legal innovation. The firm not only created a new revenue stream but did so in a way that is scalable and measurable, providing a blueprint for future initiatives (such as potentially launching similar AI-based fixed-fee offerings in other domains of law). This case illustrates how careful organisational change management, combined with tech-savvy process engineering, can transform legal services in a way that benefits both the firm and its clients, with risks managed and value demonstrated at each step.

Problem: A large international law firm (with major offices across Europe, Middle East, and Asia) found its legal technology portfolio had become bloated and fragmented. Over time, different practice groups and regional offices purchased their own tools to meet immediate needs – resulting in over 30 software applications being in use firm-wide. There were multiple platforms serving the same function: for instance, three different contract analysis tools across offices (one team used Kira, another Luminance, another a home-grown solution), several knowledge management systems, overlapping research databases (subscriptions to Westlaw, Lexis, vLex, etc.), and various workflow or project management tools. This sprawl led to inefficiencies: lawyers had to learn different systems depending on which team or location they worked with, support and maintenance was costly, and volume licensing discounts were not maximized. The CIO also suspected that many tools were under-utilised or even redundant, wasting budget. The firm wanted to cut unnecessary IT spend and consolidate on best-in-class tools, but needed a data-driven way to do it that wouldn’t hamper operations. EPF V3.2’s REVIEW and ASSESS stages were used, leveraging the Technology Business Management (TBM) framework to analyse and optimize the IT spend with a focus on business value.

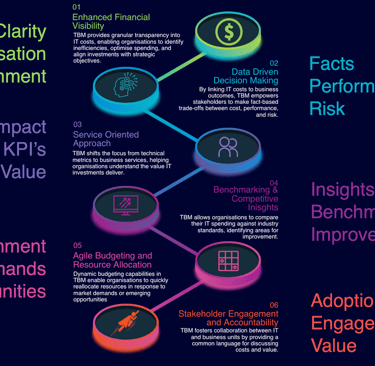

EPF Review Stage – TBM Cost Transparency Analysis: EPF began by creating a comprehensive inventory and cost map of the firm’s technology, following TBM principles. Technology Business Management (TBM) is a discipline and framework that provides a standard taxonomy and approach to link IT costs to business value . Using TBM’s taxonomy, EPF classified each application and service by its category (e.g., Collaboration, Practice Management, Document Management, Research, etc.) and by the business capability it supports (e.g., “Contract Drafting,” “Litigation support,” “Knowledge sharing”). They gathered financial data on each tool: annual licensing fees, infrastructure costs, number of users, and which departments were using it. This process was akin to creating a “Bill of IT” for the firm – a detailed bill showing how much was being spent on each IT service, much like an invoice that could be shown to business unit leaders . The TBM approach emphasizes transparency, and indeed once EPF compiled the data, the firm was able to see, often for the first time in one view, exactly how much was spent on, say, contract tools in total across the firm, or how the costs of legal research databases compared to their usage.

EPF also evaluated utilisation metrics where available: for instance, they looked at login statistics or query counts for research tools, number of matters managed in each project management system, etc., to gauge how heavily each was used. Benchmarks were applied where possible (EPF drew on industry benchmarks or vendor data for utilization rates, cost per user, etc., where the firm’s own data was lacking). Throughout this review, EPF engaged both the IT department and the lawyers/end-users – not only to collect data, but to understand qualitatively why certain tools were chosen or preferred. This was important to contextualize the numbers (e.g., a niche tool might have few users but those users find it mission-critical for a certain practice area).

The output of the Review stage was a set of data-driven insights and visualisations: a heat map showing areas of tool redundancy, charts of cost per active user by tool, and lists of tools ranked by total spend. One striking finding, for example, was that the firm had duplicate subscriptions in several categories: they paid for three e-signature platforms across different offices, when consolidating to one could achieve the same business outcome at lower cost. Another finding was that some expensive tools had very low adoption – for instance, a sophisticated matter management system was being used by only one practice group (others stuck to email and Excel), raising the question of whether to invest in roll-out or to drop it. By employing TBM’s standardised cost categorization, EPF could present these findings in the language of both IT and finance, making it clear where money was not optimally spent. Essentially, the firm’s IT spend was transformed from a “black box” of disparate expenses into a transparent, fact-based view that could be interrogated .

EPF Assess Stage – Rationalisation Roadmap & Business Case: With the data in hand, EPF moved to the Assess stage, focusing on identifying opportunities for cost optimisation without sacrificing capability. Using TBM’s value lens, they aimed to shift resources from redundant “run the business” expenses to higher-value uses. Key assessments and recommendations included:

Tool Consolidation: EPF identified categories where multiple tools did the same job. For each, they recommended the best candidate (based on functionality, user feedback, and cost effectiveness) to become the standard. For example, if three contract review AI tools were in use, and one had the highest accuracy and was already deployed in more offices, that one might be chosen as the global standard while the other two are retired. This promised not only license fee savings but also streamlined training and support. Cutting down from three tools to one in a category might reduce that category’s cost by, say, 40% due to economies of scale and elimination of duplicates. EPF showed that consolidating overlapping systems could allow negotiating better enterprise deals with vendors (leveraging the firm’s full user base for volume discounts).

Eliminating Under-Used Tools: EPF recommended decommissioning software that showed low usage and provided marginal value. For instance, the firm had a legacy knowledge management platform that few lawyers actually used (perhaps due to a newer system in place); its maintenance could be dropped. Another example: if two high-cost legal research databases were both being maintained, but analysis showed one was hardly ever accessed (maybe because lawyers preferred the other), the firm could cancel the under-used one. EPF’s data revealed such opportunities clearly – e.g., if a tool cost £100k/year but was used by only 5 attorneys occasionally, that cost per active user was exorbitant and likely unjustifiable. Removing or scaling down these would contribute to significant cost savings (e.g., 8% of the IT budget annually saved) while having little negative impact on operations. This aligns with TBM goals of 3-5% budget optimization through informed decision-making – EPF’s plan actually targeted even higher savings by tackling obvious redundancies.

Optimise “Run” vs “Change” Spend: A TBM insight is differentiating spend that is for “running the business” (keeping the lights on) versus “changing the business” (innovation). EPF found that an overwhelming majority of IT spend was on maintaining these myriad tools (“run”), leaving little for new projects or upgrades (“change”). By cutting down the run costs through rationalisation, the firm could free funds to reinvest in strategic technology. EPF’s proposal explicitly highlighted that savings from consolidation should be partly reallocated to innovation – for instance, implementing a new AI-driven knowledge search that the firm had been considering, or upgrading cybersecurity – rather than simply cut from the budget. This framing helped leadership see the exercise not as just cost-cutting, but as value reallocation to higher-impact tech. It resonates with the TBM concept that optimising run budget can fuel growth and innovation .

Chargeback/Showback for Accountability: EPF also recommended introducing a “showback” mechanism internally – essentially, using the Bill of IT data to show each practice group leader how much IT cost is attributed to their group (in terms of software usage, support, etc.). This transparency (a TBM best practice) would drive more accountability and prudent use of resources. When lawyers see that “Tool X costs €200 per user per month and only half the team is using it,” they have incentive to either use it fully or agree to drop it. In time, the firm could even implement chargeback (allocating IT costs to P&Ls of departments), but initially showback was sufficient to change behavior. National Grid’s TBM case, for example, showed how a drillable Bill of IT changed conversations to be fact-based – EPF aimed for a similar cultural shift in the firm, from “I want this shiny tool” to “is this tool worth its cost to us?”.

Using all these inputs, EPF delivered a Rationalisation Roadmap – a phased plan over e.g. 12-18 months to execute the changes. It prioritised “low-hanging fruit” (quick wins where a tool could be cut with minimal disruption) in the first 3-6 months, and more complex consolidations (which might require data migration or user retraining) in later phases. Each recommendation came with a brief business case and impact analysis. For example: “Retire Tool A and migrate its users to Tool B – expected annual saving €50k, one-time migration cost €10k, no loss in functionality. Risks: need to train users of Tool A on Tool B; mitigation: training sessions scheduled, pilot migration in one office first.” By providing this level of detail, EPF ensured the firm’s management had confidence in moving forward. They also highlighted the total expected savings – e.g., if fully implemented, the roadmap might cut 40% of the applications and save around 8-10% of the IT budget annually (say, €1M out of €12M), which could then be reinvested or contribute to the firm’s bottom line. Notably, TBM benchmarks often cite around 5% optimization , but law firms with extreme fragmentation can achieve higher; EPF’s data backed up these projections (for instance, by eliminating duplicate vendor contracts and unused licenses, a large chunk was saved).

Implementation and Risks: EPF didn’t just hand over the plan – they also advised on implementation tactics, recognising the change management challenges here. Law firms can be change-averse, and some senior partners might have personal preferences for certain tools. To mitigate this, EPF proposed forming a Technology Steering Committee that included influential partners from each practice area to oversee the rationalisation. This committee was presented with the TBM data, making the case that rationalisation was in everyone’s interest (because savings could fund things that benefit all, and a simplified toolkit would make lawyers’ lives easier). By involving them, EPF helped turn potential detractors into decision-makers in the process, increasing buy-in. Communication was key – users of tools to be phased out were informed well in advance, with explanations of why and how they would transition to the new standard tools. Adequate training and support was planned for those transitions to minimize frustration (for example, if a certain office’s folks had to switch research platforms, training sessions and cheat sheets were provided).

Data migration risk was addressed for any systems being retired: EPF worked with IT to ensure that any data (documents, know-how, etc.) in a decommissioned system would be archived or moved to the surviving system so nothing was lost. In some cases, they found that overlapping systems actually duplicated data (e.g., two knowledge bases might have much of the same content), so consolidation also improved knowledge sharing by ending silos.

Outcome: As the firm executed the roadmap, benefits quickly materialised. Within the first year, they cut roughly one-third of the applications, including completely eliminating 5 systems and consolidating 4 others into 2. The annual IT spend dropped by 8.4% as projected (for example, through cancelled contracts and better negotiated deals for the consolidated tools) – resources that the firm re-budgeted partly into new strategic projects (one notable reinvestment was the development of a legal AI chatbot for internal use, which previously had no budget). The CFO and CIO, armed with TBM reports, could now have value conversations with practice heads: instead of just saying “we need to cut IT costs,” they could say “we’re spending €X on these overlapping tools for your group, let’s direct some of that €X into a tool that actually brings more value to you.” This shift to fact-based discussion improved alignment between IT and the lawyers, a classic outcome of TBM transparency .

For the lawyers and staff, after the initial adjustment period, there were noticeable improvements. The digital workplace became simpler – fewer logins and systems to juggle, a more consistent user experience across offices. For example, all lawyers now used the same document automation tool, so internal training sessions and tips could be shared firm-wide, and best practices developed. The “cognitive overload” of learning multiple software was reduced, which lawyers appreciated. New joiners found onboarding easier as well (previously, joining one office vs another might mean learning a totally different tech stack).

Morale in the IT department improved too: supporting 30+ applications meant being stretched thin, but after consolidation, they could focus on deeply supporting the chosen core systems and proactively improving them, rather than firefighting across many platforms. The IT team also established a TBM Office function (even if informal) to continuously monitor technology value. They continued producing quarterly Bill of IT reports for management, sustaining the transparency. This ongoing practice prevents “tool creep” from recurring – any new software requests are now evaluated in light of the whole firm picture to avoid slipping back into silos. Essentially, the firm’s culture around tech investment became more disciplined, with a common language of cost and value introduced by TBM (e.g., partners became aware of the concept of cost per user, and started asking “do we really need this if we already have something similar?” which was a big mindset shift).

In summary, through EPF’s Review and Assess using TBM, the firm achieved a leaner, more cost-effective IT landscape without losing functionality. In fact, by consolidating, they often chose the best tool in each category, so many users gained improved functionality (like switching from a less capable tool to the firm-wide standard that was better). The financial savings were tangible and redirected to innovation, directly supporting the firm’s competitive edge (like investing in AI and knowledge platforms). The case demonstrates that applying a structured IT management framework (TBM) in a law firm can translate technology spend into business terms and drive meaningful change. What was once an opaque sprawl of IT expenses became a well-understood portfolio of services delivering value. This rationalisation not only saved money but also enhanced the firm’s agility – with a simplified stack, they can more easily upgrade or replace components in the future and roll out firm-wide solutions. Ultimately, the firm’s lawyers can work more efficiently with less IT friction, and management has confidence that their tech investments are aligned to actual needs and are under control, which is a significant strategic benefit in the evolving legal market.

4. Launching a Client-Facing AI Compliance Service (Engage + Orchestrate Stage)

5. Rationalising a Fragmented Legal Tech Stack with TBM (Review + Assess Stage)

Contact Us for Business Transformation

Get in touch to start your transformation journey today.